|

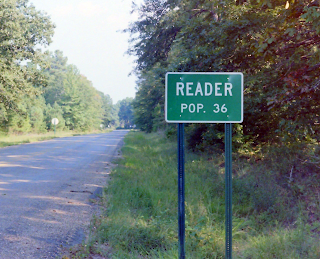

| Photo Credit: Wikipedia |

Twenty

years ago, somewhere near mile marker 187 in Glacier National Park, the

alternator on our car went out. After hitchhiking to the nearest gas station

and having the car towed to Kalispell, MT, we learned that the closest

alternator supplier was 250 miles away in Spokane, WA. Since it was the start

of the Fourth of July weekend, the part would arrive in 4-5 days. Our stay in

the area turned out to be much longer, however, because the wrong part was sent

the first time.

For

several reasons, the holiday wait was not a disaster. One reason was the great

quantity and variety of reading material where my husband and I were staying.

That’s when my husband was anointed as the Designated

Reader. He did and still will read nearly anything: the Economist, Guns and

Ammo, old New Yorkers, National Geographic, Better Homes and Gardens, Popular

Mechanics, Fine Woodworking, Readers’ Digest, and Sunset Magazine. He will also

read cookbooks and sailing manuals, how to build hay bale houses, and anything

about the history of the English language.

From years

of experience, I know it’s great to have a designated

reader in the house. I regularly enjoy a constant flow of articles, links,

book reviews, travel tips, and new studies on museums, gardening, travel,

birding, literacy, old houses, book arts, and more.

Not surprisingly, I also believe

every museum should have at least one designated

reader. Museums operate in a dynamic community, educational,

and economic context. Subsisting on ideas re-circulated internally is hazardous

to a museum’s health. To stay current, be prepared for inevitable bumps, and challenge

themselves, museums must have a steady diet of ideas, information,

and perspectives from in and outside the field. Every museum needs staff and

trustees who think, see, and read beyond the museum walls, carry forward what’s visible in the

rear-view mirror, and look past the horizon. Learning individually and

collectively as a museum must be fully integrated into its DNA.

Designated readers contribute to a

vibrant learning life for a museum.

Years ago

Minnesota Children’s Museum’s CEO, Ann Bitter, came up with a related idea. Our

Strategy Team (a.k.a. the STeam Team a.k.a STeam) became, in effect, the designated readers for the museum. We added some

subscriptions to what the Museum already had and assigned one magazine to each

STeam member to read each issue, select, and distribute interesting and

relevant articles to others on STeam as well as across the museum. Those articles

became fodder for discussion, leads on new technology, challenges to our

thinking, and sources of new strategy. In addition to museum publications, we

covered business, education, technology, children’s literature, and family

leisure. I still have a article, The New Work of the Nonprofit Board” from Harvard Business Review

(1996) that I refer to even now.

With her

monthly Museum Education Monitor, (MEM)

museum educator, consultant, and editor Christine Castle has been the designated reader for museum education for

11 years. The final issue of her on-line subscription service was in December

2015. MEM’s goal was to enhance the development of

theory and practice in the field by both academics and museum workers. Each month, Christine invited readers and subscribers to

contribute research and resources

in museum education worldwide on a related theme

such as Adults and Older People, and Science, and Internships. Each

month the publication delivered resources including on-going research, blog

postings, on-line journals, print journals, new books and media, and

professional development. Citations, links, abstracts, and author contacts for

each entry made the material easy to access as well as extensive and perfect for designated readers at museums everywhere.

I take my

own role of sharing articles, resources, studies, and blog posts very seriously and

I enjoy it. Perhaps somewhat like a designated

reader myself, I pass out articles and send links to colleagues and clients

in areas related to a project: strategic planning, stakeholders, engaging

parents and caregivers, or documentation. Sometimes I give a book to a museum

at the end of a project to continue the discussions and contribute the museum's

library. An issue that several museums are dealing with often becomes the

starting point for a Museum Notes post that’s likely to include links

to articles, studies, or reports.

There is,

however a limit to how much a single reader who visits only occasionally can

cover– especially compared with the varied interests and perspectives that a

dozen readers in a single museum who talk and work together everyday can

generate. Moreover, a disposition to read is needed in every museum all the time. A museum that aspires to be a learning organization needs–and

deserves–multiple strategies to advance this. The designated

reader is one strategy to activate and support.

From observing the reading and learning lives of museums, I think instituting a designated reader strategy is helped along in a number of ways.

From observing the reading and learning lives of museums, I think instituting a designated reader strategy is helped along in a number of ways.

• Start

with 2 designated readers, and possibly more depending on the

size of the museum. Float the idea first to get a sense of staff’s interest and

response. Invite and encourage people to volunteer to be designated readers; the enthusiasm of a natural-born designated reader is invaluable. Be

ready, however, to assign the role to get started. Integrate the designated reader into the

organizational, team, and working group structure as STeam did.

• Align

with the museum’s priorities. Every museum has multiple priorities, the topics, or interests, highlighted in the

strategic plan, improving quality, or stepping up to community challenges. Making these explicit helps a museum. These are the areas a museum needs to build capacity, provide professional development, develop a shared understanding. These are areas for the designated reader. Sustainability? Access and inclusion? Community engagement?

Family learning? Performance measures? Social entrepreneurship?

And yet, as

important as aligning reading with museum priorities is, …

• …Read

widely and stretch. Create a richer reading mix with both familiar sources and more adventurous finds. In addition

to reports from the field like TrendsWatch 2016 or IMLS's Brain-Building Powerhouses, read the LEGO Foundation’s Cultures of Creativity, and check-out reports on museums worldwide. Find readings in other sectors: healthcare, business, technology, education, as well as arts and culture. Read current research and museum classics by John Cotton Dana and Stephen Weill. Select different, alternative, approaches and perspectives on a

particular topic–free admission, internships, branding, docent training, or museums' role with schools.

• Shape

a process for reading and sharing. A process for reading, sharing, and discussing is likely

to evolve with time based on a museum’s practices and its own learning style. But thinking

through an initial process built on what generally works well at a museum will

help set a smooth course. • Who’s

involved and in what ways? • Should readings be distributed to those whose work relates most

closely to a topic or does an interesting article or report on a tangentially

related topic serve as a friendly provocation? • Would a protocol for discussion be helpful? • How can we actively engage

people with the ideas? Through a structured discussion or an informal

conversation at a staff meeting? • Do we want to connect threads and themes? Apply

ideas to our work? • Should discussion be facilitated by one person? What

metabolism for reading can we maintain?

• Commit

resources to the designated reader effort.

Reports, blogs,

plans, needs assessments, research, and sometimes journals are available on

line and free. It is, however, unlikely that all of the key areas a museum intends

to dig into will be available for free. Subscriptions are a good and,

relatively speaking, small investment in the museum’s future; budget for

subscriptions. Anticipate and support the time that is necessary to read and

discuss articles and studies. Create a kind of museum library, in binders, on the server, or in an alcove.

• Expect everyone to read. Keeping up with information

and ideas is not the domain of one department, usually the education

department. Besides, museums are emphatically places of learning. They expect their visitors

to read labels and learn. So why wouldn't all staff, volunteers and trustees be expected to

read and learn?

Related Museum Notes Posts