You, however, may find it

perplexing that this joke is funny to me. And you may find it a bit worrisome

that, with a sense of humor like that, I am writing about humor.

But that’s humor. Some

things are funny. Sometimes. To some people. But we all love a good laugh. We

love to tell jokes, repeat riddles, sneak in a pun or two, read the comics

section before the rest of the newspaper, play practical jokes and just try to

make others laugh. Even people who can’t tell a joke to save their lives

appreciate humor.

As important as humor is,

however, we tend to think of it in a narrow category, distant from learning.

School is for learning. Humor is for after hours. Who does not remember a

teacher’s challenge, “Is that a joke you would like to share with the rest of us?”

“Serious” books are referred to in hushed, respectful tones, while comic books

are dismissed, concealed, forbidden and enjoyed.

Informal learning settings

such as museums, and perhaps children’s museums especially, are wonderful

exceptions to this dubious dichotomy. People construct their own meanings and

museums are places where learning experiences are driven by the learner. Along

with the cognitive, intellectual, part of experience, museums also try to tap

into the affective, feeling, dimension of experiences. Affective goals

increasingly guide exhibit and program projects. Exhibits and programs

sometimes tap into the humor visitors bring with them to museums.

Children’s museum settings

are well-suited for humor. Because they invite learning at its broadest, they

are natural places for the full range of children’s emotional lives, their

senses of humor, laughter, and the learning that accompanies them.

Too Funny for Words

Humor and laughter are

zesty tonics for living. They release built-up tensions, allow expression of

ideas and thoughts otherwise difficult to express, facilitate coping with

trying circumstances and bond people with a shared experience.

Like many of the rich,

complex, interesting phenomenon such as creativity or play, humor is hard to

define. It includes puns, humorous comments, comic verse, riddles and physical

comedy. While we are certain we recognize humor when we see it, humor is hard

to define or even categorize. In fact, we frequently confuse it with or mistake

it for other familiar, humorous situations such as play, a baby’s laughter or

an animal’s antics.

For instance, humor is

often part of the fun and the pleasure of play. In play, however, humor and

laughter are secondary to the pursuit of the activity itself. A baby’s face

first blossoming into a smile around 4 to 8 weeks is more than gas. But it’s

not humor. It’s a milestone towards ensuring she will have the love and

attention of her parent, but it’s not about entertaining them.

Finally, though we find

other animals’ lolling, scratching, climbing and tailchasing to be funny, we do

not share a good laugh with them. Humor and jokes are pretty much the exclusive

domain of humans, although it seems that language-using apes demonstrate a

sense of humor remarkably similar to that of a preschooler. The laughing hyena

notwithstanding, the purely physiological act of laughing is unique to humans.

Humor is human. It begins

at home and it begins early in life. It is, in fact, a kind of “nervous

laughter.” The capacity for humor is built into the nervous systems of humans

and is one of those mental activities that serves to maintain an optimal level

of stimulation that keeps humans alert and active in the world. Too little

stimulation and the world is bo-ring; too much and it’s a mental meltdown.

A study conducted in the UK determined that a shared environment rather than shared genes

accounts for a similar sense of humor among family members. Not every family is

funny, but family members are funny – or not funny – in similar ways. You’ve

seen it before: a gaggle of look-alike-siblings giggling together at the oddest

things. And most likely they think the same about you and your siblings.

At the risk of defining

the undefinable, reducing the rich variety of humor to one type and taking all

the fun out of it, we can simplify humor a bit. In a theory proposed by Paul E.

McGhee (1979), much of humor – and, in particular, humor for children – relies

on a few critical conditions. First, humor comes from incongruity and from what

is perceived as wrong or oddly juxtaposed. Something unexpected, inappropriate,

unreasonable, illogical or exaggerated must be present for laughter to roll.

Second, an understanding

of how things should be is a

prerequisite for humor. There must be a clear enough expectation of how a

situation should be or how things should work in order to recognize when an

incongruous event has been substituted for the expected one. We know that from

birth on, infants try to master the basics of what does and does not belong

together in their world. This constant sorting out prepares them from the

get-go for enjoying humor. Drawn to investigating the world and parsing the new

until it becomes familiar, children are building knowledge. Repetition, whether

looking at a mother’s face, dropping handfuls of oatmeal on the floor or

bouncing on the dog, helps children grasp basic understandings about events,

objects and ideas.

A third condition for

humor is a state of playfulness, a readiness for fun. The same joke told after

a tire blows out rather than during happy hour at the bowling alley probably

won’t get any laughs. Finally, for children, at least, there must be an ability

to engage in fantasy. In make-believe play the child explores what happens when

inappropriate objects or events are inserted into different situations. The

endless possibilities of creating odd combinations such as “putting your mother

on the ceiling” produce a fascination with fantasy activity.

Kidding Around

Just like the story of The

Three Bears, the effort required to “get” the joke has to be “just right.” Too

much mental effort takes the fun out of funny. But, jokes that are too easy to

figure out also aren’t funny because we get the point immediately. While puns

are not always funny to older adolescents and adults because they are too

simple, they are a hoot to 5 and 6 year olds who have recently mastered

language. Laughter and smiles are the rewards for the effort required to

reconcile the double meaning of “hoppy birthday” on a birthday card.

The onset of humor in

babies appears to be surprisingly young. A child’s earliest experiences with

humor may be as early as 10 months. These are typically private moments with

humor because the child hasn’t yet developed the language facilities for

sharing the experience. But like a silent movie, the film’s rolling. The baby

conjures up a memory of an image of an object, as a baby about 12 months is

able to do, and creates a discrepancy between what is usual. Simply bringing

the “wrong” image to bear on a given object, like holding a shoe to the ear as

if it were a phone, a child suspends the usual rules. Escaping laughter and

giggles attest to the fact that the child “gets” it.

In a baby’s first year,

experiences with certain games such as peek-a-boo and chasing have many of the

conditions of humor. Resolution of there/not there and running away provide the

unexpectedness or incongruity that tickle little funny bones. The accompanying

smiles and laughter indicate a likely appreciation for the humor of the situation.

Hardly has the child

grasped with certainty which objects belong together and which don’t when he

starts to mix them up, enjoying nonsense words, mismatched objects and events.

Maybe you’ve noticed. Did you ever put your shoes on your hands or mittens on

your feet to entertain a toddler? Even as young as two years old, children

recognize – and laugh over – the inappropriateness of an action directed toward

an object.

Young children not only have their own sense of humor, but

they also actually produce humor at an astonishingly early age and rate. In a

study by Lori Moglia (1981), children 15 to 45 months old produced a joke about

every eight minutes. Looks, facial expressions and giggles accompanied all

jokes making it clear to others that humor, not misunderstanding, was involved.

For instance, a child might say, “The dog is saying ‘meow’” and laugh or might

say, “This is a poison cookie” and giggle.

While there are widespread

individual differences among children on the humor front, patterns through

stages are pronounced. During the earliest stage, a toddler will treat a toy or

object as if it were something else. For instance, at about 2 years old, one of

Piaget’s children picked up a leaf and held it up to her ear and talked as if

the leaf were a telephone. As a child’s language develops, incongruous labeling

of objects and events becomes the source of humor. Word mastery allows the

child to playfully change the names of objects, substitute the word cat for dog, repeat rhyming words or use nonsense words for the correct

word.

When the child realizes

that words actually refer to a class of objects and certain characteristics,

they find humor in mixing-and-matching characteristics, often based on the

incongruous appearance of things. A cat with elephant ears, barking and wearing

a skirt is funny to a 4-year old. The first step towards adult humor occurs as

a child becomes aware that something has 2 meanings, one based in normal

circumstances and one based in a set of incongruous circumstances. Riddles such

as “When is it time to go to the dentist?” (Two-thirty) appeal to 7-year olds

who proudly choose the joking answer.

A Climate of Gentle Humor, A Climate for Learning

Children’s museums almost effortlessly offer a climate for

both humor and learning. They are places where children feel safe, take risks

and combine the familiar and the novel. Sensory and object-rich settings invite

exploration, imitation and fantasy play. And experiences within a wide

developmental range allow children to practice and master emerging skills and

concepts. While we readily know these as conditions that encourage learning,

they also invite humor. The surprise and delight that humor brings keeps us

awake for other possibilities, like learning something.

Humor requires a friendly setting, especially for the very

young. Putting a flower-pot hat on your head in the costume area, quacking like

a duck or playing Twister® with 50 other people isn’t as easy as it looks for

all children. If a setting is too unfamiliar, a child may feel anxious rather

than excited about transforming objects, being confident of her ability to

discern incongruity, or possibly being the source of someone else’s humor.

Allowing a child to watch, join when ready or participate from the sidelines

can squeeze giggles out of caution.

Because children’s

exploration is directed by their senses, their humor is often inspired by

appearances or sounds. This is a fine match with the multi-sensory and

multi-dimensional settings of children’s museums rich in sights, sounds and

textures. More than silliness is at play as a child replays his voice as though

he were singing opera in a canyon or a shower; looks at himself in a concave or

convex mirror; or plays with a pig puppet that has wings.

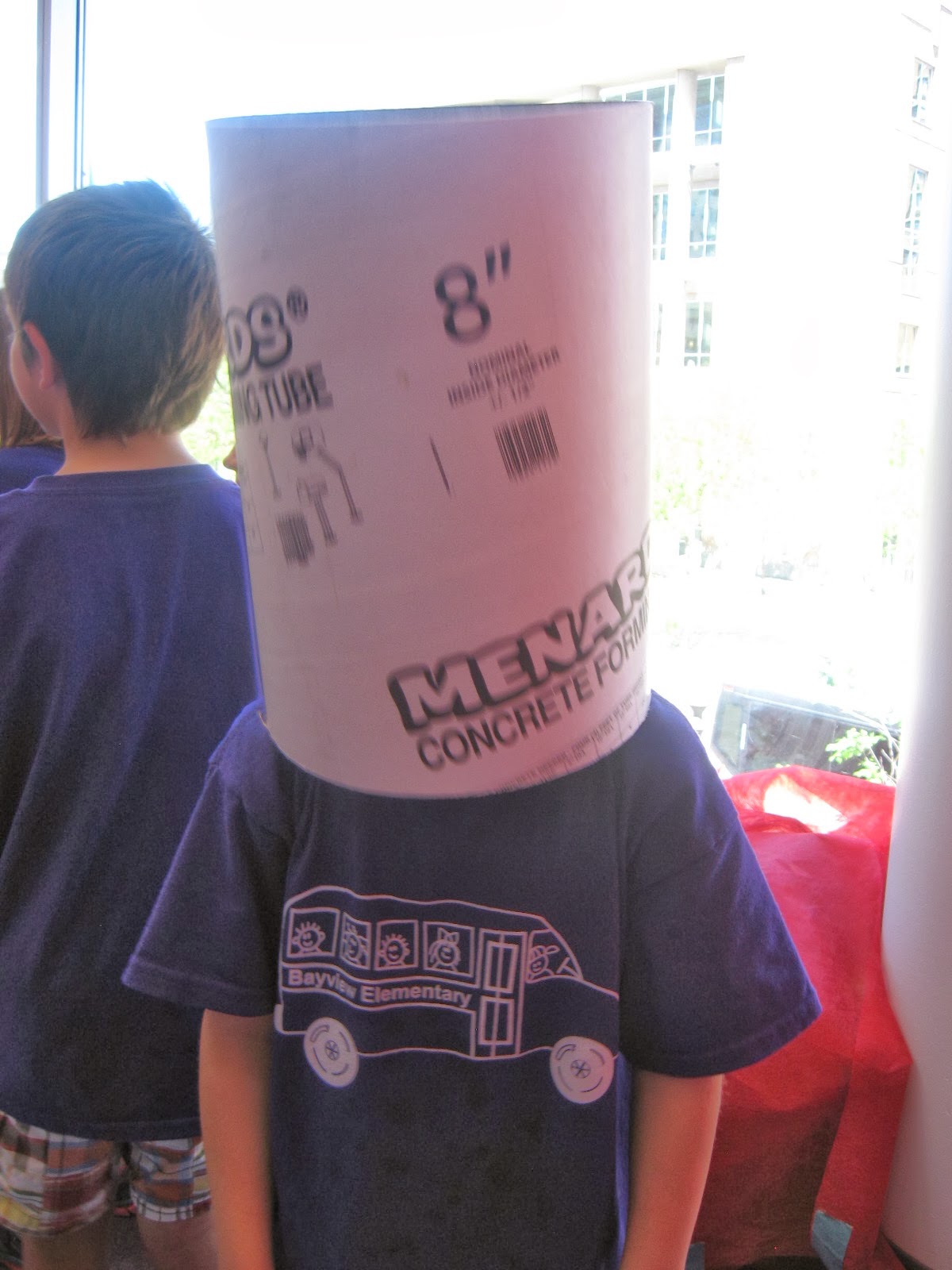

Puppets, props and costumes, tools and giant toys fuel a

child’s imagination and humor. A child pretends a toy car is something absurd,

like a bug-mobile. A child delights at the great visual humor of a

mix-and-match animal with the tail of a fish, the torso of a zebra and the head

of a bird. Children of all ages enjoy the situational humor of playing “air”

guitar in front of the green screen showing an underwater or hospital scene.

The Funny Things that Make Me Think

|

| Pittsburgh Children's Museum (Wired) |

As well suited as children’s museums are for humor, actually

transforming humor into a tool for learning is as hard as telling a joke really

well. Museums must carefully hit the mark with humor, knowing when, how, and

how much humor to present, using it purposefully––but not too

purposefully. Humor commanded is humor killed.

Children’s museums can’t make everything funny and they

can’t tell all the jokes. They can make room for humor in the building,

exhibits, programs, performances, and greetings. But they must then step aside

and allow visitors to construct their own meanings from experiences and engage

in the give-and-take with families and other visitors to generate laughter and

understanding.

Just as important as matching the intellectual effort for

“getting” a joke, is finding the right tone for humor. Humor’s value is

cancelled when it is over child’s heads, in poor taste or mean. Too raw and

parents may be put off; too sanitized and it’s babyish. Finally, humor can’t be

a substitute for being honest and straightforward with children about what’s

happening. It must hew the line between being a motivator for learning and a

sugar-coated disguise for learning.

The trick in using humor

as a tool for learning is for the riddle or cartoon to be purposeful. Humor

must serve a larger goal and directly connect to the concept being presented.

There is no lack of good jokes, cartoons, riddles or visual puns. But as with

any activity in an exhibit, matching a joke to a concept is both is essential

and challenging.

Riddles in exhibit text

can help make connections in funny ways. What has a mouth but can not talk?

could be a riddle in an exhibit on geography. What has a tongue but can’t

speak? might be in an exhibit on shoes. Not only can the content of jokes

reinforce learning, but so can their forms. Jokes help preschoolers practice

the question-answer format that is part of emerging literacy. Even if a

three-year old’s attempt at a riddle isn’t funny to his audience now, he’s

practicing the structure for a joke that some day will win a laugh.

Especially for older children,

jokes and cartoons invite problem solving. Jokes require attention to all of

the available information, depend on logic, and require seeing things in more

than one way, but make their point through humor. What ‘s the difference

between a dog and a marine biologist? might teach a thing or two about a marine

biologist as well as teach about attributes, differences and homonyms. (*Answer

at the end.)

With so much humor based

in incongruity and understanding things in more than one way, jokes and riddles

provide children with tremendous opportunities to see something from different

perspectives. Sometimes the shift is between real and make-believe; between

probability and possibility; and between two meanings of the same word. “Humor,

fundamentally, is a game of double perspective, and helping children take new

perspectives is an important part of their intellectual development,” George

Forman, Professor of Education at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst has

observed.

The laughter that

accompanies humor is also a tool for learning. When incongruity results from

phenomenon behaving unpredictably, a gleeful tee-hee might be the “ah-ha” indicating

that the child understands something is awry. Watching a ball roll up an

incline might produce a guffaw that suggests the child “gets” the problem––but

not the solution. Listening to laughter can be a tool for staff, offering

insights in how to extend an activity into an understanding.

Humor walks in the door everyday with visitors and will

continue to as long as the conditions are ripe. Rich settings with lots of objects

inspire a child to play and transform things from how they should be to how

they could be. They inspire a new knock-knock joke; someone to toss a hat on

the Bernoulli Blower; or build the “apple tower,”––that’s a seven-year old’s New

York version of the Eiffel Tower with an apple on top.

What’s

So Funny?

When we see humor in action in exhibits and programs, in

text, and on the faces of visitors and staff, we see the power and potential of

humor to invite delight and spark learning.

Years ago the Bay Area

Discovery Museum (CA) had an exhibit on insects. At one station visitors could

pick up a small set of bug boxes, hold them to their ears and listen to the

sounds of different insects. One box invited visitors to hear the sound of

beetles and played a Beatles tune.

“The Far Side of Science,”

an exhibit by the California Academy of Sciences took on the popular

cartoonist, Gary Larson. Visitors could be examined under a giant microscope.

When they did, they saw a big hairy eyeball over head, peering down at them.

At The Boston Children’s Museum (BCM), fake poop in the

toilet got a smile and a laugh. Independently of the popular theme of bodily

fluids as a source of humor, discovering the unexpected in a public setting –

and a museum, no less – jiggles a giggle from even the most adult visitors.

The Children’s Museum of

Maine (Portland) explored humor in their exhibit, HA! HA! HA! – Laughter Around the World. Visitors could deposit or

withdraw jokes at the Laughter Bank, measure the frequency and range of a laugh

at the Laugh-O-Meter, or create their own comedy at “Le Petit Comedy Club”,

complete with a microphone, studio audience, canned laughter and a real comedian’s

script.

In the ZoomRoom at the

Creative Discovery Museum (Chattanooga) and in other ZoomRooms, the ZoomVid

offers kid-tested riddles that knock kids’ funny-bones. What does a pig put on

his sunburn? Oinkment.

What’s so funny at your

museum? Think of the giggles emanating from your visitors, the humor that walks

in the door with everyone of them. Pick up a few new funny ideas to add to the

mix. Visitors will love, laugh and learn from it.

Answer: (A dog wags its

tail. A marine biologist tags a whale.)

Related Posts

Book Notes

- McGhee, Paul E. Humor: its origin and development. 1979. WH Freeman and Co. San Francisco, CA 1979.

- Moglia, L.A. Stage Development of incongruity humor and the use of play cues in the play of preschool children. (Unpublished Honors Thesis) Bucknell University. .PA. 1981.

This post first appeared

in Hand to Hand (Fall 2000, Volume 14, Number 3), a quarterly publication of

the Association of Children’s Museums. Reprinted by permission of the

publisher. To learn how to obtain the full publication, visit www.ChildrensMuseums.org.