|

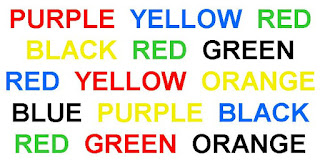

Stroop Test: The automatic behavior–word reading–has to be inhibited in favor of a less practiced task –naming the ink color.

|

“I’m the baby, so I have to cry.”

You might not think that this is music to a future employer’s ears, but it is. This statement, typical for a young child engaged in make-believe play, reflects early evidence of executive brain functions, a collection of cognitive skills that allow us to exert control over our thoughts, manage our attention, and restrain impulses in order to reach our goals.

Executive functions are located in the pre-frontal cortex of the brain, an area that keeps track of goals, engages in abstract problem-solving, and moderates appropriate behavior. Referred to variously as cognitive functions, self-regulation, and cognitive control, executive functions are characterized as orchestrating, weaving, mediating, and integrating other functions. Neuroscientists, scholars, psychologists, educators, and parents have helped increase awareness of executive brain functions, moving discussion from child development textbooks and Young Children to The New York Times and Wall Street Journal.

A deep internal mechanism facilitates children and adults engaging in thoughtful, goal-directed behavior. There are two aspects to these functions: stop and go. On the one hand, self-regulation is the capacity to exert control over thoughts and impulses and, when necessary, to interrupt doing something. On the other, self-regulation involves the capacity to engage in another behavior because it’s needed, even if it’s less attractive. In the pretend play example above, the child is subordinating behaviors she would like to engage in–perhaps pretending to eat a lollipop–and is substituting a behavior she would rather not engage in–crying because she sees herself as well passed the age of crying. For an adult executive brain functions means not relying on habits of perception while forcing the brain to use its power of observation; in the graphic above, it is reading the word red when it is written in green.

Focus, Switch, Resist, Think

The human need for complex, flexible regulatory systems that can cope with a wide array of environmental conditions means that the development of self-regulation begins early, takes place over an extended period of time, and requires substantial external support. (Berk, Mann, and Ogan. 2006)

Executive brain functions develop early–appearing around 7-12 months–and rapidly during the preschool years through dynamic interactions between brain activity and experience. Development of language plays a key role in the strengthening of these cognitive controls supported by hints and cues from adults, support from the environment, and play. Some executive functions improve during adolescence becoming more efficient and effective with increased mastery over thinking, emotions, and behavior. During the 20’s, executive function skills are at their peak. In later adulthood, these skills begin to decline, some having earlier, and others later, onset of impairment.

Different models for executive functions break down and describe them with some variations. In her recent book, Mind in the Making: The Seven Essential Skills Every Child Needs, Ellen Galinsky identifies and explores 5 executive functions that work together in various combinations of skills such a perspective taking, making connections, and problem solving.

• Focus is being alert and paying attention. Focusing on something allows you to use what you already know and maximize getting information from it.

• Cognitive flexibility is being able to flexibly switch perspectives, change the focus of attention, or adjust behavioral responses as conditions or context change.

• Working memory is actively holding information in your mind while manipulating it: relating one idea to another; relating what you’re listening to now to what you just heard; and relating what you are learning now that you learned earlier.

• Inhibitory control is controlling attention, emotions, and behavior to achieve a goal; being able to resist a distraction, an impulse, or an attractive stimulus.

• Reflection is stepping back, considering alternatives and then acting, thinking about someone else’s thinking, or the goal you want to accomplish.

Everyday Executive Functions

Our world of abundant distractions and novel situations makes executive brain functions valuable, if not essential, as 21st century skills. They help us to be alert, orient to a task, and focus; keep relevant details in mind and concentrate for an extended period of time. With the help of executive functions, we exert self-control and override responses to attractive stimuli. We resist the urge to answer a cell phone or text message while reflecting on a painting. We pass up an extra chocolate because it conflicts with another goal–the diet. We don’t check email or Facebook every 5 minutes because we need to finish a report.

Self-regulation is also thought to be heavily involved in navigating novel, dangerous or technically difficult situations. Functions like planning or decision-making; error correction or troubleshooting are needed when responses are not well-rehearsed, novel sequences of action are required, or strong habitual response must be subordinated.

|

| In imaginary play, children use objects to help manage impulses and their behavior |

|

But self-regulation is not just for high tech levels of distraction or high-test situations and it's not primarily for adults. Significantly, self-regulation is thought to have an especially important role in school performance and beyond. Young children translate plentiful everyday cues from people and the environment into information to regulate behaviors and emotional tension. Early on, they learn to calm themselves, inhibit the urge to grab, wait for their turns, remember rules, and persist in challenging tasks. Active, intentional self-regulation develops during early childhood through language, make-believe play, and older children and adults demonstrating appropriate behavior and offering hints and cues.

Children’s intentional self-regulation predicts school success and may actually account for a greater variation in early academic progress than intelligence. In a well-known 1972 study by Walter Mischel of how self-control interacts with knowledge, four-year olds were offered a marshmallow. If the child could resist eating the marshmallow, the child was promised two marshmallows instead of one. The ability of a four-year old to resist the temptation of a second marshmallow turned out to be a better predictor of future academic success than his or her IQ score.

Executive function skills are relatively malleable and can be improved. Just how malleable and by what means, however, are not well established. Still, research that is underway is gradually indicating how we might take advantage of these capacities to help children and adults develop skills for school, for social situations, and for life.

One well-known program is Tools of the Mind, a research-based early childhood program that promotes children’s intentional and self-regulated learning to build strong foundations for school success in preschool and kindergarten children. The program uses several strategies critical for supporting children’s development of self-regulation: scaffolding, reflective thinking, self-regulation activities, and mature dramatic play. Other evidence that self-regulation can be taught in the classroom emerges from Blair and Razza’s study of low-income pre-school children which indicates that curricula designed to encourage children’s self-regulation skills can promote early academic progress. Adele Diamond’s research has shown that diverse activities can benefit children’s executive functions. Among other things, her lab studies facilitative factors such as bilingualism and school programs, and, the role of dance, storytelling, and physical activity. Practice also helps. Repeatedly performing basic exercises in cognitive self-regulation boosts executive functions for children or adults, although these results have not been as impressive outside of the lab.

Executive Brain Functions In Museums

Before I dug into reading about self-regulation, I had a general impression that their significance was primarily to young children and during early childhood. There’s no doubt that the early years are critical for development of executive brain functions, but that’s a limited view. Likewise, the classroom is not the only setting for promoting executive functions.

Robust executive brain functions play a critical role for all us across the life span and across life settings, including museums. Weaving together social, emotional, and intellectual capacities, executive functions are active in the highly social, strongly evocative, sensory and information rich environments of museums. Furthermore, strong executive brain functions for children and adults engage with the strategic, learning, financial, and community interests of museums. Skills used in social interactions (emotional self-regulation) as well as in thinking (cognitive self-regulation) are valuable and relevant to museums across a range of interests and activities. A few, just a few, are highlighted below noting some the related executive brain functions involved

• Museums value the active, extended engagement of visitors in exhibits and programs. Spending more time or getting more involved with an object, phenomena, or activity, and trying a variety of activities maximize the information learners draw from it. Persistence plays a role, whether following an activity to its natural conclusion or persisting in the face of challenges and is supported by paying attention (focus) and sticking with something after a failure (inhibitory control).

• Museum experiences often involve learners in taking another perspective. Children and adults explore another culture, are immersed in an historic context or time period, or adopt a perspective of being the dog or a pirate in a play sequence. This involves inhibiting one’s own thoughts or feelings (inhibitory control) and considering those of others as well as seeing a situation in a different way (cognitive flexibility). Taking another perspective can also apply to museum staff viewing the interests of the intended audience in a different way.

• Making connections is a goal established for many museum experiences. An exhibit or program highlights practical application to learners’ everyday lives, interprets features of objects in the collection, creates the conditions for building structures, invites exploration of how something works, and encourages creativity. Making connections is critical to making sense of a situation and relies on recognizing similarities and differences (cognitive fluency), using rules (working memory)–from simple to increasingly complex–and applying and recombining elements in various and inventive ways (cognitive fluency).

|

| Even small gizmos build on multiple executive functions |

• In working on an experiment in a hands-on lab, building a wind tube at garage studio, or operating an electric crane in a building area, learners move through a sequence of steps in a process and keep on track to reach a goal through planning. Creating a marble-run, building a castle, or creating paper medallions relies on sustained attention (focus); keeping a number of things in mind at once (working memory); making corrections as the mind watches itself (reflection); and resisting the impulse to skip steps in the interest of a larger goal (inhibitory control)

Executive brain function can even support fundraising goals. Patty Belmonte, Executive Director at Hands On! Children’s Museum (Olympia, WA) has shared how she took the children’s museum’s case for play to the business community as part of the museum’s capital campaign. Initially, the response was less than Patty hoped. When she reframed it, however, to relate play’s role in developing executive brain functions, business leaders heard her. They immediately recognized the skills and functions they needed in their employees from her description of self-regulation: attentional focus, perspective taking, making connections, following rules, and persistence in the face of challenges.

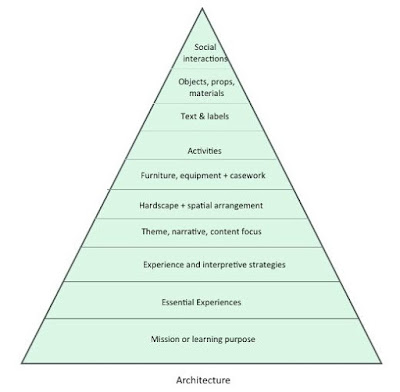

How to incorporate executive brain functions into planning visitor and learning experiences may not be immediately obvious. Nevertheless, museums currently use many strategies to develop experiences that encourage self-regulation. Museums prepare the environment, engage visitors, prepare staff and volunteers to give cues and hints; encourage social interactions among visitors; and invite extensive physical and cognitive interactions with objects and phenomena. These approaches, and more, point towards the abundant and varied opportunities museums have to act on their missions, benefit their audience, and serve their communities by deliberately taking advantage of the capacities executive brain functions offer.

What are you doing in your museum to strengthen executive functions and the skills museum learners use?

References and Resources

• Berk, L. E., Mann, T. D. and Ogan, A. T. (2006). Make-believe play: Wellspring for development of self-regulation. In Dorothy G. Singer, Michnick Golinkoff, and Hirsh-Pasek, K. (eds.) Play = Learning: How play motivates and enhances children’s cognitive and social-emotional growth. Oxford University Press: New York.

• Galinsky, E. (2010). Mind in the making: The seven essential life skills every child needs. Harper Studio: New York.

• Zimmerman, B. J. (1994). “Dimensions of academic self-regulation: A conceptual framework for education.” In Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance: Issues and Educational Applications, eds. D.H. Schunk & B.J. Zimmerman, 3–24. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

• Mischel, W., Shoda, Y. and Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science. New series. Vol. 244 No. 4907 (may 26). 933-938.

• Blair, C. and Razza, R.P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, Vol 78, Issue 2. (The Pennsylvania State University).

• Diamond, A. and Lee, K.. (2011). Interventions shown to aid executive function development in children 4 to 12 Years Old. Science 19 August. Vol. 333 no. 6045 pp. 959-964.

• Diamond, A. and Barnette, W. S., Thomas, J. and Munro, S. (2007). Preschool program improves cognitive controls. Science 30 November.

• Tough, P. Can the right kind of pay teach self-control? New York Times. Sept. 27, 2009.